Instructed Eucharist 2019 Notes as requested

THE INSTRUCTED EUCHARIST (2019)

St. Michael the Archangel

Matthews, NC 28105

The Celebrant will announce:

Please be seated.

Let us gain a better understanding of the chief and central act of Christian worship:

“the Lord’s Own Service / on the Lord’s Day.”

First let us speak briefly concerning the clergy preparation:

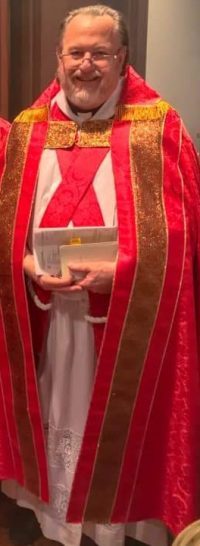

Significance of the Liturgical Vestments

- Vestments detach us who wear them from everyday thoughts and concerns (since they are not worn in ordinary activities).

- It puts the individuality of the one who wears them in an order to emphasize his liturgical role.

- It is a statement that the liturgy is celebrated “in persona Christi” and not in the priest’s own name.

1) WASHING OF HANDS: Before vesting the priest washed his hands not only for hygienic purpose, but a signification of the passage from the secular to the sacred.

Scriptural Reference: Washing the Hands is equivalent to removing the sandals before the burning bush (cf. Exodus 3:5).

At Washing the Hands

CLEANSE my hands, O Lord, from all stain, that, pure in mind and body, I may be worthy to serve Thee.

2) THE AMICE

Scriptural Reference: The amice is understood as “the helmet of salvation,” (Eph 6:17) that must protect its wearer from the demonic temptations, especially evil thoughts and desires, during the liturgical celebration. This symbolism is clearer in the custom followed by the Benedictines, Franciscans and Dominicans, who first put the amice upon their heads and then let it fall upon the chasuble or dalmatic.

While putting on the Amice:

PLACE, O Lord, the helmet of Salvation upon my head to repel the assaults of the Devil.

3) THE ALB

Definition: It is the long white garment worn by the sacred ministers, which recalls the new and immaculate clothing that every Christian has received through baptism.

Scriptural Reference: The alb (from latin, albus = white) is a symbol of the sanctifying grace received in the first sacrament of Baptism and is also considered to be a symbol of the purity of heart

While putting on the Alb

CLEANSE me, O Lord, and purify my heart, that, being made white in the Blood of the Lamb, I may attain everlasting joy.

The prayer is a reference to Revelation 7:14:

4) THE CINTURE

Scriptural reference: The cincture represents the virtue of self-mastery, which St. Paul also counts among the fruits of the Spirit (cf. Galatians 5:22).

While putting on the Girdle

GIRD me, O Lord, with the girdle of purity and quench in me the fire of concupiscence, that the grace of temperance and chastity may abide in me.

5) THE MANIPLE

During the celebration of the Holy Mass it is worn on the left forearm.

It was used to wipe away tears or sweat, medieval ecclesiastical writers regarded the maniple as a symbol of the pain and toils of the priesthood.

Scriptural Reference: Psalm 125

While putting on the Maniple

GRANT me, O Lord, to bear the light burden of grief and sorrow, that I may with gladness take the reward of my labor.

6) THE STOLE

Definition: It is the distinctive element of the vestment of the ordained minister and it is always worn in the celebration of the sacraments and sacramentals. It is a strip of material whose color varies with respect to the liturgical season or feast day.

Together with the cincture and the maniple, the stole symbolizes the bonds and fetters with which Jesus was bound during his Passion.

While putting on the Stole

GIVE me again, O Lord, the stole of immortality, which I lost by the transgression of my first parents, and although I am unworthy to come unto Thy Holy Sacrament, grant that I may attain everlasting felicity.

7) CHASUBLE

This vestment is proper to the one who celebrates the Holy Mass.

While putting on the Chasuble

LORD, who hast said, My yoke is easy, and My burden is light, grant that I may so bear it, as to attain Thy grace. Amen.

By vesting properly, a priest physically, psychologically, and spiritually prepares as best He can for the sanctity of the mystery that will unfold.

Once properly vested, prayers are said by all participating at the altar…

The Processional

At our 10:30 service we normally have a musical processional.

We read of this tradition back to OT times:

for King David would write while he was in exile in Ps 42: (4)

I pour out my soul in me:

“For I had gone with the multitude,

I went with them to the house of God,

With the voice of joy and praise,

With a multitude that kept the holyday.”

So today, we will join King David as we process into Christ’s Church– now let sing hymn 55 while we Process into this House of God…

The Procession enters the Church as usual

and the narrator makes his way to the pulpit immediately.

When the procession is completed, say:

NARRATOR: Please be seated.

This morning, we are participants in what is known as an Instructed Eucharist.

The Service will be as usually done FOR 10:30 am service, but with the addition of some explanations of the various parts.

Obviously, there is much more to the Holy Eucharist than can easily be covered here, so we will only touch on some of the more important points.

Eucharist: the very word comes from the Greek word meaning ‘Thanksgiving.’

This name is one of the most ancient names for this Service,

which was instituted by the Lord Jesus Christ Himself when He took bread

and wine and said, ‘Do this in remembrance of me.’

Our doing “of this,” then is in obedience to His command to the Apostles at the Last Supper,

a command universally obeyed by all Catholic and Apostolic Christians.

The Holy Eucharist is also known by other names – the Lord’s Supper, the Holy Communion, the Divine Liturgy, the Holy Sacrifice, the Holy Mysteries, the Breaking of the Bread, and the Mass –

ALL refer to the very same identical Service.

We have four accounts of the Eucharist in Holy Scripture found in

1) I Cor (11:23-25)

2) Mt (26: 26-28)

3) Mk (14:22-24)

4) Lk (22:17-20)

We see it was celebrated by the early Church as seen in the Book of ACTS (2:42,46)

The book of Acts even shows it being celebrated possibly daily (Acts 2:46) and certainly weekly (Acts 20:7.)

From the very beginning, the Eucharist has been part of Christian worship…

It may even be implied in Genesis (14) as Melchizedek brings forth bread and wine.

We read in Justin Martyr’s first apology which described the Eucharist in 163 A.D. as the bread and wine: “is the body and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

The word Mass, which is common in the Western Church, was

retained in the first Book of Common Prayer of King Edward VI in 1549.

In that original masterpiece, the Prayer Book title of the Eucharistic

Service reads:

‘The Supper of the Lord, and the Holy Communion,

commonly called the Mass.’

The name Mass is also very ancient, having been used by Saint Ambrose of Milan, an early Church Father, as early as AD 385.

The Holy Eucharist then: is the worship of Almighty God our Father

through the One Sacrifice of Jesus Christ, with all the members of His Body,

the Church, in union with Him.

Since it is the central act of Christian worship, it should be celebrated with all honour, dignity, reverence, and beauty that the Church can muster.

As we begin, let us contemplate the place where we celebrate this

glorious Mystery. The Altar, on which the Consecration of the true Body

and true Blood of Christ takes place, is the centre of our worship. This is

why the Altar is the most prominent piece of ecclesiastical furniture in orthodox Anglican Churches.

It is placed at the eastern wall of the Church, ‘oriented,’ signifying the ancient belief that our Blessed Lord will return from the East.

Facing East is an ancient tradition, grounded in sure knowledge about the Second Coming, first told us by the Lord, and then repeated by an angel after the disciples had just seen the Lord ascend into heaven:

“For as the lightning comes from the east and shines as far as the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man” (Matthew 24:27)

Saint Augustine of Hippo calls facing East, ‘facing the Lord.’

In the Service, the priest and people have usually face the same way

all together offering the same Sacrifice to God through Jesus Christ.

It is difficult for the Priest to lead prayer when facing the people; because he becomes a focal point for prayer; as the people are facing him!

Therefore, along with the people he faces the altar with them.

The Altar is treated with great reverence, for it is an Image of Christ,

(the altar is even marked with five incised crosses, symbolizing his five wounds upon the cross,)

and represents the Sacrifice Our Lord made for us on Calvary.

On the Altar, that very same Sacrifice of Christ is re-presented to the Father and to the faithful.

‘For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you show forth the Lord’s death until he comes’ (I Corinthians 11).

A frontal, in tapestry or in the colour of the day, hangs down the front

of the Altar.

The fair linen on the Altar is white to represent purity.

The square linen Corporal, from the Latin ‘corpus,’ ‘body,’ on which the Body of the Lord and the sacred vessels rest, is also white.

The two sides of the Altar are referred to as the Epistle (right hand when you face the Altar) and the

Gospel (left hand) sides – from the custom of reading the Epistle and the

Holy Gospel from their respective sides.

Upon the Altar rest the vessels used for the celebration of Mass:

The Paten, plate, and Chalice, cup, are neatly arranged on the Corporal,

the Paten on top of the chalice

and the Purificator a small fair linen cloth used to wipe the Chalice during communion,

is spread over the top of the chalice and then the paten on top of the Purificator.

The Pall, a square piece of board covered in linen, is used to cover the Chalice during the service, in order to keep any foreign objects out of the cup.

It is arranged on top of the Paten and underneath the veil.

Covering the vessels is the Veil, a beautiful cloth having the colour of the day or feast,

and the Burse, a pouch into which the Corporal is placed after communion (this is the custom followed at St. Michael’s.)

The Missal, or Altar Book, is placed on the Altar with its stand or desk. The Missal contains all of the prayers of the liturgy.

The Tabernacle, which contains the consecrated Elements of the Body

and Blood of Our Lord, is located on the Altar at its centre.

In it is to be found the Blessed Sacrament, Our Lord’s Real and Objective Presence in the Holy Mysteries.

Therefore, when entering or leaving the church building, or when passing before the Altar,

we should genuflect or bow in adoration of Our Lord really present in the consecrated Gifts.

The Sacrament of the Altar is reserved in our parish Church both for the communion of the sick and those who cannot attend Mass.

The other sacred furniture we will discuss and has practical use, as well as having symbolic meaning,

the credence table holds items needed for the Celebration and is located to the right of the Altar on the Epistle side.

Among the items on it are the cruets containing wine and water, a bread

or host box, and a lavabo bowl and towel (‘lavabo’ means ‘wash’ in Latin).

In this parish the celebrant and his assisting ministers, and the

acolytes, say prayers of preparation, based on Psalm 43, before the Mass begins.

They are referred to as the ‘Prayers at the foot of the Altar’ or simply as ‘the Preparation.’ In our parish, these prayers are usually said in the vestry room, before the Service begins.

In a sung Eucharist, a processional hymn is sung as the choir,

acolytes, and clergy process to their appropriate places in the nave and

sanctuary.

During the Procession, in honour of the Lord’s Sacrifice, we bow our heads to the processional Cross as it passes by.

The Holy Eucharist has two parts:

- the Ante-Communion or Liturgy of the Word, as it is also called, and

- the Communion or Liturgy of the Eucharist

Everything from the very beginning of the Mass through the Creed can be called the Fore-Mass or the Mass of the Catechumens.

This first part, called the Liturgy of the Word, is based on the ancient service of the Jewish Synagogue,

consisting of the reading of Scripture and prayer.

The Mass begins with the Collect for Purity which we pray in our hearts while the priest prays aloud –

asking God to cleanse us of all thoughts which would bar the way to our worship.

The Collect for Purity serves in our service both as an introductory invocation to the entire rite

and as an immediate preparation for the examination of conscience in the Commandments that follow.

Then follows the Introit, a passage of Scripture establishing the liturgical theme of the day which includes the Gloria Patri or ‘Glory be…’

On many Sunday’s the choir will sing the Introit…if not, it is said by the Celebrant:

PAUSE

The reader then remains at the pulpit while the

priest prays the Collect for Purity and Introit.

Once he is finished, then the Rector says:

Now the priest recalls God’s will for us as he rehearses the Ten

Commandments (the first Sunday of the month) or the Summary of the Law (Deut 6:4-5 & Lev 19:18).

Recognising that we have failed to obey our heavenly Father as we should, we ask for His mercy as we say or sing a version of the Kyrie Eleison, ‘Lord have mercy upon us.’

The Kyrie Eleison has been said for over 1700 years as found in early Christian Writings (Apostolic Constitution.)

PAUSE

The reader remains standing at the pulpit

the priest says the Decalogue or Summary

and Kyrie Eleison.

When the Kyrie is ended, say:

Reader Continues:

The Collect of the Day is a summary of the aspirations and petitions

suggested by the Feast or Mystery being celebrated.

As always, when gathering the prayers of the Church, collecting them, and offering them to God on behalf of the people, the priest faces the Altar –

he makes Intercession before the Lord, facing towards the East.

In ancient tradition, three collects were usually said; in many cases our Prayer Book directs at certain times that at least two collects be said.

PAUSE

The priest prays the Collects of the Day.

Afterwards, the narrator continues, saying:

If we have an Old Testament reading, it is usually the 1st Lesson reading of the day’s Morning Prayer (we normally do not have public MP on Sundays.)

Following the Old Testament reading,

we read from the Book of Psalm, unusally responsively ½ verse to ½ verse (this Psalm is also normally chosen from the Daily Office readings for Morning Prayer.)

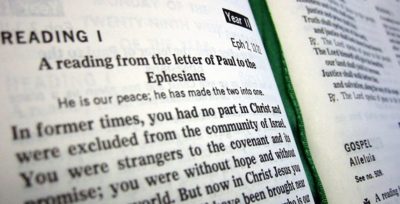

The Lesson or Epistle, as it is called in the Holy Eucharist,

is generally read by one of the Ministers of the Sanctuary:

the celebrant himself, a deacon if one is present,

or as we normally practice – one of the layreaders of the parish.

If it is a Solemn Celebration, with the traditional three Sacred Ministers (like at Easter or Christmas,) it is customary for the Subdeacon to intone the Epistle and the Deacon to chant the Gospel.

The Collect of the Day, the Epistle, and the Gospel form the major propers of the day because they fit a particular feast, mystery, or other celebration.

The living Word of God, Jesus Christ, is proclaimed and manifested to us in His written Word, the Holy Scriptures.

PAUSE

The reader remains standing while the

Old Testament, Psalm, and Epistle is read.

Immediately after the Epistle,

The narrator continues:

While we sit for the Epistle and for the sermon,

we stand for the reading of the Holy Gospel – to give honour to our Blessed Lord who Himself is the Word of God Incarnate.

The Altar Missal is moved from the Epistle side to the Gospel side, symbolising the carrying of the Good News (which is what the word Gospel means) to those who do not know Christ.

Occasionally, the Gospel will be processed out into the congregation to be read among the people.

Many of the faithful make three little Signs of the Cross as the Holy Gospel is proclaimed.

A small Cross is traced with the thumb of the right hand –

first on the forehead, in the same place where it is traced at our Baptism;

a second one is traced across the lips,

and a third one is traced on our heart.

We pray in effect that the Gospel may be in our minds, on our lips, and in our hearts.

(The Crossings show first our intellectual acceptance of the Truth, second, our readiness to confess it with our speech, and third, our heartfelt attachment to it.)

The responses before and after the Holy Gospel, are either said or sung.

The only time they are not used is during the reading of the Passion at Holy Week.

PAUSE

The reader remains standing for the Reading of the Holy Gospel.

When it is finished,

the Reader says:

The ‘Creed commonly called Nicene’ is said or sung on all major Feast Days and on all Sundays of the Christian Year.

It is the essential corporate statement of our Faith in the Blessed Trinity and the Incarnation,

authoritatively summarising what is taught in Holy Scripture.

This Creed is the great Creed of the whole Undivided Catholic Church, East and West.

It is used at the celebration of the Eucharist in all Apostolic Churches.

This Creed is the product of the first two Ecumenical or General Councils of the ancient Undivided Church:

the First Council of Nicea in AD 325 and the First Council of Constantinople in AD 381.

The only two changes made to this Creed: first, a mistaken omission in the 1549 Anglican Prayer Book of the word ‘holy’ from the description of the Church as One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic, which Anglicans have since corrected;

and second, the addition of the words ‘and the Son’ to the phrase ‘who proceedeth from the Father’ in the version of the Creed used in the Western Church.

This addition is known by its Latin form, Filioque (fill – ee – oh –kway).

It does not appear in the original version of the Creed or used today by the Eastern Churches.

Worshippers at Mass speak with their actions as well as with their words as they confess their Faith.

Each traditional action has a meaning.

At the mention of the Name of Jesus and at the phrase ‘worshipped and glorified’ in the Creed, we bow our heads in worship.

As we say the words ‘and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man,’

the Incarnatus of the Creed, we bend our right knees all the way to the

floor in honour of God’s act of love and humility in sending His Son to assume our human nature.

With this genuflection, we honour the Incarnation of Jesus Christ.

Finally, the Sign of the Cross is made at the last phrase to express our hope for the Resurrection and ‘life of the world to come’ and acts to seal our profession of the Creed.

PAUSE

Again, the reader remains at the lectern for the Creed.

The celebrant leads in the saying of the Creed…

When it is ended, Reader says:

After the Creed the Prayer Book directs that it be “declared unto the People” any announcements such as schedule for upcoming week, along with “other matters.”

The Prayer Book directs that the sermon be preached, but today since our instructed Eucharist is the sermon, no sermon proper will be given.

Celebrant will say a few words…

Continues:

We now begin the second and most sacred portion of the Holy Communion Service. The rite of this latter half corresponds to the four-fold action our Blessed Lord performed at the Last Supper:

- He took the Bread – called the Offertory

- He gave thanks – called the Consecration

- He broke the Bread – called the Fraction

- He gave It to His disciples – called the Communion

The Mass of the Faithful, the Holy Communion, also called the Liturgy of

the Eucharistic Sacrifice,

reproduces by its four-fold shape the

institution of the Blessed Sacrament.

It makes present Christ’s Sacrifice.

The first action is the bringing of the offerings to be set apart in the

liturgy,

bread and wine for use in the Holy Sacrament, and alms, as a portion

of what we have obtained through our daily labours.

The gifts represent the offering of our lives, and of all creation, to God to be

united to Our Lord’s Sacrifice -which will be sacramentally made-present in the Mass.

The celebrant prepares the gifts for the Consecration, offering private prayers at the Altar as each element is readied.

The priest first offers the bread to God, and then mixes wine and water in the chalice.

The mixed chalice of water and wine symbolises the union of the divine and human natures in Christ,

and also symbolises our union with Christ through the Blessed Sacrament.

The mixed chalice also reminds us of the blood and water which flowed

from Christ’s side on the Cross (S. John 19).

The priest next offers the contents of the chalice to God, and then blesses the gifts with the Sign of the Cross.

After this, the priest washes his hands, the ‘lavabo,’ asking God to cleanse him from his sins.

Finally, before noting the intentions of the day’s Eucharist,

he offers a ‘secret’ prayer, which, like the collect, gathers everyone’s prayers and establishes the theme of the day.

At the presentation of the alms, they and the unconsecrated elements of bread and wine are offered with a hymn of thanksgiving, at St. Michael’s it is customarily the Doxology.

PAUSE

The offertory sentence is read by the celebrant.

The Anthem ensues while (or if) the alms are collected.

After the gifts are presented at the Altar,

the narrator continues:

Turning to the people, the priest announces the intentions for which

this particular Mass is offered.

Then, the beautiful exchange, the Orate Fratres (oh-rah-tay frat-ress) or ‘Pray Brethren’ is made between celebrant and people,

concluding with the invitation by the celebrant to all those present to pray for the ‘whole’ that is ‘healthy’ state of Christ’s Church.

We now pray for the unity of the Holy Catholic Church, and for those in

sacred and secular authority, especially remembering our bishop, with whom

in the Eucharist to share ecclesiastical communion.

We pray for the present congregation and for the living in every need and necessity; we pray

also for the Holy Dead, that they may grow in God’s holiness and love.

Finally we pray for our union with the whole Communion of Saints through Jesus Christ our unique Mediator.

Pause:

The reader remains standing as

the priest prays for the special intention of the Eucharist

and then he says a Prayer for the Whole Church.

After the ‘Amen,’ say:

In approaching God, we must recognise our sinfulness and confess our individual sins by joining together in the General Confession.

We cannot worthily worship God or receive Our Lord’s Body and Blood unless we are in a state of repentance and amendment of life.

The celebrant will give you an Invitation to a penitential preparation.

As the rubric in the Prayer Book directs, any who are to receive Holy Communion MUST make this confession as they kneel.

The priest, or the bishop if he is present, then obeys Our Lord’s command to the Apostles and pronounces the forgiveness of sins to those who are truly penitent.

In this moment, the Absolution, the Bishop or priest again functions as the Icon of Christ at the Altar –

for bishops and priests are given authority and power from Christ to forgive sins in His Name, as we read in Saint John chapter 20.

We make the Sign of the Cross on ourselves as we receive the Lord’s Absolution, which means ‘loosening from sin’ or ‘unbinding.’

Following this, the priest reminds us of God’s grace and mercy with the Comfortable Words.

The Comfortable Words, although indeed comforting, are more than that. The word ‘comfortable’ means ‘strengthening.’

PAUSE

The Priest will give the Invitation…

Kneel and say the General Confession

He will rise and give the Absolution

He will then give the Comfortable Words

The Prayer of Consecration, Canon of the Mass, will now follow. Before it begins, here are a few remarks:

An exchange of versicles and responses, called the Sursum Corda

(Latin for ‘lift up your hearts’) which since the earliest times in all historical liturgies of East and West have opened the Consecration Prayer.

This then leads to the Proper Preface which brings together the dutiful praise and thanksgiving of the universal Church both living and dead – at all times and in all places –

and of the heavenly host into a common hymn of sheer and timeless adoration to the holiness of God,

which commemorates the theme of the day.

Following is the Sanctus, which is an expansion of an ancient Hebrew prayer in which God is glorified as Thrice Holy (Holy, Holy, Holy.)

Christians understand this hymn as an act of worship offered to the Holy Trinity.

Following that, we say the words used to welcome Our Lord when He entered Jerusalem, ‘Blessed is He that cometh in the Name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.’

It is a traditional custom to make the Sign of the Cross on oneself when the words, Blessed or Hosanna, are said or sung.

Pause

The Priest will say the

Sursum Corda (Latin for ‘lift up your hearts’)

Proper Preface

Sanctus, Holy, Holy, Holy.)

And now to not interrupt the rest of the service, I will describe the rest of the service, then we will partake…

The Canon proceeds to recall before God the Father the redemptive work of our Lord Jesus Christ on the Cross

and then recites the Words of Institution, or the Institution Narrative, which is the heart of the Eucharistic Prayer.

By the very Words of Christ and the power of the Holy Ghost, the bread and wine are consecrated into the living Body and Blood of Christ.

In this action, the one perfect Sacrifice of Christ, which He once offered on the Cross and eternally exhibits in heaven,

is made-present to us, pleaded, for us, and applied to us in the Eucharist.

The priest, representing Our Lord, says:

‘This is my Body, This is my Blood.’ The bread and wine become what Our Lord says they are.

After each element is consecrated, it is raised on high for all to see and adore. Jesus Christ’s true Body and Blood are really, truly, and objectively present under the forms of bread and wine.

A small bell is rung. The eyes may be cast down at the ringing of the first bell as the priest genuflects or bows in adoration of Our Lord.

You may raise the eyes and behold your Lord and Saviour at the elevation, and you may say quietly with Saint Thomas, ‘my Lord and my God’ at the ringing of the second bell.

Bow the head as the priest again genuflects or bows at the ringing of the third bell.

This action is done at the elevation of the Sacred Host and repeated at the elevation of the Chalice.

Next, the Sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ is re-presented to the Father in the paragraph entitled, ‘the Oblation.’

With ‘these thy holy gifts which we now offer unto thee,’ the sacramental Memorial of Christ is set forth before the Father on behalf of the whole Church –

in thanksgiving for the redemption wrought by Our Lord.

This part of the Canon is described by its ancient name, the Anamnesis (ah-nahm-nee-suhs) that is,

remembrance or Memorial: ‘Do this in remembrance of me.’

Under the form of bread and wine, Our Lord presents in the midst of His Church the realities of His life, death, resurrection, and ascension.

These historical events are brought into our time and space, through the Holy Sacrament,

so that we may be joined to them and receive their benefits.

The Eucharistic Sacrifice is not a mere mental or psychological remembrance of a dead person or a past event:

it makes the living Christ and His entire work of redemption present to us here and now.

In the mystery of the Eucharist, Our Lord joins us to His Sacrifice and makes us one with it, thus offering us in Himself to His Father.

The Eucharist (Mass) is Christ’s Offering for us, and we are gathered into it. The Eucharist is, simply, remission of sins, life, and salvation,

for it is nothing other than Christ Himself.

Another part of the Canon is the ‘Invocation’ or Epiklesis (epi-klee-sis),

in which we ask the Father to bless and sanctify His gifts with His Word and Holy Spirit,

so that the Bread and Wine may become the blessed Body and Blood of His Son.

From now on in the Service, the Blessed Sacrament is often called the Body and Blood of Christ, not just bread and wine.

The Holy Ghost transforms the Bread and Wine into what Our Lord proclaims them to be, His glorified life, His Flesh and Blood.

We next present ourselves as a living sacrifice as we ask for the Eucharist to be applied to us and to the whole Church for the forgiveness of our sins.

Many worshippers bow at this time.

A moment later we may make the Sign of the Cross as we ask to ‘be filled with thy grace and heavenly benediction.’

Then we ask that the Lord will accept ‘our bounden duty and service’ in spite of our sinfulness.

At the words ‘although we are “unworthy’ some worshippers strike their breast, along with the celebrant,

to show that they are sorry that they are not worthy.

The Prayer of Consecration concludes with a doxology to the Holy Trinity. We should offer a resounding AMEN at the end of this Great Prayer.

Then joining in the prayer Our Lord taught us to pray, we prepare to make our own Holy Communion.

As the Celebrant begins the Lord’s Prayer, he then read a silent prayer and re-joins for the finishing verses of the Lord’s Prayer.

Before the administration of Communion, the priest breaks the Sacred Host into two pieces in a re-enactment of Our Lord’s breaking of the bread at the Last Supper.

This is called the Fraction.

The ancient and traditional Peace then takes place as the celebrant makes the Sign of the Cross over the chalice with a small portion of the Host.

As he does so he says: ‘the peace of the Lord be always with you.’

The people respond: ‘and with thy spirit.’

The priest then places a fragment of the Host into the Chalice at this time, signifying the reunion of the Body and Blood of the Lord in His Resurrection.

This is called the commingling or commixture.

We then offer the Prayer of Humble Access, so named originally in the Scottish liturgy,

in which we acknowledge that we approach the Altar trusting in God’s mercy, not in our own worth,

and we ask that we be united with Him.

This prayer, based on Saint John chapter 6, is the most dramatic affirmation of the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament found in the Anglican liturgy.

It is the Flesh and Blood of Christ we adore and receive.

A traditional hymn, the Agnus Dei (O Lamb of God) follows.

It is customary to sing this hymn whenever the Holy Eucharist is sung.

This hymn and the prayers that immediately follow stress our Lord Jesus truly is present in the Blessed Sacrament.

Note that the Agnus Dei and the presentation of the Gifts, the Ecce Agnus Dei, directly address the Lord Jesus.

Otherwise, the Mass is always addressed to God the Father.

Next we make our Holy Communion, answering the invitation:

‘Behold the Lamb of God,’ which is taken from Saint John chapter 1.

The people respond at the presentation of the Holy Gifts: as the Priests says ‘Lord, I am notworthy that thou shouldest come under my roof, (and the people respond) but speak the word only and my soul shall be healed.’

This beautiful prayer is based on the prayer of the centurion to the Lord Jesus in Saint Matthew chapter 8.

As Our Lord under the form of Bread and Wine is presented to us, we may sign ourselves with the Sign of the Cross as the priest proclaims,

‘Behold!’ a response, ‘Lord I am not worthy,’ we may strike the breast as a sign of unworthiness and faith.

It is traditional to extend an invitation to receive Holy Communion to those Christians who have been both baptised and confirmed by a Bishop in Apostolic Succession.

As we approach the Altar to receive Our Lord, we should bow or genuflect, that is, kneel down on our right knee,

before walking down the aisle toward the rail, for ‘every knee shall bow

and every tongue shall confess that Jesus is Lord’ as we are taught in Philippians chapter 2.

It is customary to make the Sign of the Cross on oneself after receiving the Host and after receiving the Chalice.

Please remember either to receive the Sacred Host in the hand, your hand acting as a plate and not handling it with your fingers,

for crumbs (the Body of our Lord) may fall to the floor,

or to receive It directly in the mouth.

Guide the Chalice to your lips with your hand in order to assist the priest, deacon, or lay reader.

After the Holy Communion of the Faithful, the sacred vessels are cleansed during what is called the ‘ablutions’

as great care is giving to clean the paten and chalice and consume all consecrated elements

with any reserved being placed in the Tabernacle.

Of note: once the elements are consecrated and become the body and blood of our Lord,

the Priest will traditionally keep his forefinger and thumb together to insuring no crumbs may fall from his handling of the host.

During the ablutions the celebrant may have the server pour a drop or two of wine onto his forefinger and thumb and then pour water to wash.

Then the priest will be able to open his thumb from his forefinger.

The Prayer of Thanksgiving is said in gratitude for the Mystical Feast we have shared.

We thank the Father for the gift of the Body and Blood of His Son and for our membership in the Church by virtue thereof,

in which we are empowered to do the good works intended for us.

Depending upon the time of year, “The Gloria” may be sung or said and it may be followed by the traditional Post-Communion Collects.

Finally, a Blessing is pronounced by the priest, but not before we are bidden to go out into the world in peace and thanksgiving :

Either “Depart in Peace” or ‘Let us bless the Lord.’ ‘Thanks be to God.’

The Blessing is given by a bishop if he is present.

Only a bishop or priest can give this specific blessing of the Church,

and we make the Sign of the Cross on ourselves as we receive the blessing.

A hymn is usually sung to allow the choir, acolytes, and Ministers of the Sanctuary to exit.

The worshippers stand as the procession leaves.

Then they kneel immediately to make their own silent and individual thanksgivings for Holy Communion.

Without further interruption then, we continue with the central and most sacred part of the liturgy.

STOP: The reader re-joins the service.