What is Common Prayer – by the Revd. Dr. Peter Toon

The word “common” is used in all kinds of ways, and so what do Anglicans mean by the word “common” when it is associated with public prayer and worship? Since we are referring to the worship of our Creator and Redeemer, Almighty God, we can dismiss quickly the popular meaning of “common” as that which is ordinary, undistinguished or even of inferior quality. The texts of the services and rites used before God to address him are surely intended to be of high not low quality, excellent not shabby. So the basic meaning of “common” as used in religious English appears to be “that in which the people unite.” Thus Common Prayer is public worship/prayer in which people unite in the public place, the consecrated building, for worship using an approved form of service, approved by ecclesiastical authority. And when the Common Prayer is that of a specific jurisdiction of the Church of God – e.g., a national church – then the same basic rites or services are used everywhere in that jurisdiction with minimal local variation.

If one may use an analogy from music, Common Prayer is intended to be like a hymn sung in harmony, where there is both identity and individuality operating at the same time, without the confusion that would come from singing several different hymns at once. Common Prayer leaves room for both shared and individual identity, as people attempt the same task of well-defined acts of worship according to their particular gifts. In contrast, as we shall suggest in the next chapter, multiple-service forms, on the other hand, with the best will in the world, have the tendency to degenerate into cacophony. Ironically, as we shall also note below, the loss of true common prayer can also diminish the value of other sorts of prayer, local or private, because there is no longer a common thought, knowledge, faith, or standard, by which to evaluate and improve them.

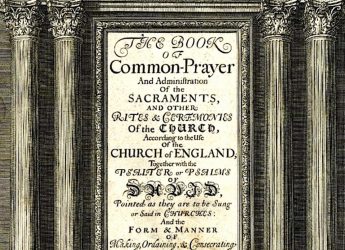

The Book of the Common Prayer

Before, and at, the publishing of The Book of the Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the Church: after the use of the Church of England (1549) “common prayer” in England referred to the Daily Offices said by the clergy and some laity in the chancel of each and every parish church. Since this was not the private office of the clergy but the public gathering of the people of the parish, it was “common prayer,” offered to God in Latin until 1549 and in English thereafter. The long title of the English Prayer Book of 1549 was necessary for it replaced the multiple service books (Breviary, Missal, Manual etc.) of the late medieval period, books which provided what is known as “the Sarum [Salisbury] Use.”

We may note that the title, The Book of the Common Prayer … after the use of the Church of England, presupposes that there is a form of prayer “common” to the whole Christian Church. What Archbishop Cranmer offered in English was the presentation of that “common” (taken as “universal”) prayer of the Christian Church after the use of a particular national church, the Church of England.

In 1552, the second definite article was removed so that the title began, The Book of Common Prayer, and from this time forwards the expression “Common Prayer” gradually came to mean all the public services in which the people united, especially Morning and Evening Prayer, the Litany and Holy Communion. Further, the expression “Common Prayer” also gradually came to mean the actual book that contained these services for they were found nowhere else at that time (no websites or CDs). Thus the expression “Common Prayer” in everyday conversation came to mean both a specific text containing services or rites used in all parishes, and also the assembling and uniting of the clergy and people to use these services to pray and worship publicly.

In the official Book of Homilies (1562) of the Church of England, there are several sermons which deal with prayer. One of these is entitled, An Homily wherein is declared that Common Prayer and Sacraments ought to be administered in a tongue that is understanded of the hearers. After explaining two kinds of prayer, the silent prayer of the heart and vocal, private prayer, we are told:

The third sort is Public or Common. Of this prayer speaketh our Saviour Christ when he saith, If two of you shall agree upon earth upon any thing, whatsoever ye shall ask, my Father which is in heaven shall do it for you; for, wheresoever two or three be gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them. … By the histories of the Bible it appeareth that Public and Common Prayer is most available before God; and therefore it is much to be lamented that it is not better esteemed among us, which profess to be one body in Christ … . Let us join ourselves together in the place

Here Common Prayer is that praise and supplication offered to God the Father with one heart and voice by the one body of Christ in the place appointed for worship and using the appointed prayer book, The Book of Common Prayer. It is important to note that private prayer is distinct from Common Prayer, for it may occur anywhere at any time outside the act of Common Prayer, or it may occur before and after Common Prayer as well as within it.

In the Fifth Book of The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, written towards the end of the Elizabethan era, Richard Hooker, the distinguished apologist for the Church of England against Puritanism, defended and commended the official English version of “Common Prayer” as found in The Book of Common Prayer (Elizabethan edition of 1559) against the criticisms of the Puritans. For him, as for the homilist, “Common Prayer” is the worship of Almighty God with one heart and voice by the one body in the one place, using a language that all understand as that is found in a rite or text in the English Prayer Book. In contrast, he shows that the preaching services of the Puritans and Presbyterians are not “common prayer” even though Christian people, who attend them, genuinely hear the Word of God and give assent to prayer offered to heaven by the preacher.

In reference to the consecrated church building and its association with common prayer, Hooker wrote:

Concerning the place of assembly, although it serve for other uses as well as this …, the principal cause thereof must needs be in regard of Common Prayer …; that there we stand, we pray, we sound forth hymns unto God, having his angels intermingled as our associates … . But of all helps for due performance of this service the greatest is that very set and standing order itself, which framed with common advice, hath both for matter and form prescribed whatever is herein publicly done. No doubt from God it hath proceeded, and by us must be acknowledged a work of his singular care and providence, that the Church hath evermore held a prescript form of Common Prayer, although not in all things everywhere the same, yet for the most part retaining still the same analogy. (V. xxv)

For Hooker “that very set and standing order itself” is obviously Common Prayer, The Book of Common Prayer (1559) authorized by Queen Elizabeth I.

One of the basic characteristics of the traditional English Common Prayer has been that there is one only rite provided for each of the public services and there is no provision for extempore prayer by the minister. While the readings from the Holy Scripture change daily, the actual service itself is virtually identical daily and weekly. There is no optional rite for Holy Communion or Baptism or for the Daily Services of Morning and Evening Prayer. Thus Common Prayer also naturally developed the meaning of the use of a common text for use not only in the one parish church but in all the churches of the one nation. And this, of course, was what the various Acts of Uniformity meant and required – unity in uniformity through use of basic Rites.

It is important to recognize the English sense of the identity of Common Prayer with the book whose title contains this expression. Writing from within the Church of England, Mr A. C. Capey has recently written:

Common Prayer belongs to the nation; it was created for us out of, and taking theological exception to, various department service-books and other documents; it was recovered for us, in defiance of the Presbyterian Directory, in 1662; it was retained for us, in defiance of William III’s desired “comprehension” (a sort of “homes-centres” ecumenical venture …) in 1689; it comfortably resisted Unitarian depredations in the 18th century; it was the linchpin of the Tractarian movement; it was only cautiously modified in 1928, in an attempt to keep the Anglo-Catholics away from the lure of the English Missal. The book belongs to us all, even if only a tiny proportion of the tiny proportion that attends church today actually prays it … .

(A. C. Capey, “Common Prayer and the Pirates” in The Real Common Worship, edited by Peter Mullen, Edgeways, 2000, pp. 68–9.)

In America this identity has been no less pronounced within the English culture not only of the Episcopal Church, but of the liberal arts in general.

Without any serious doubt, Common Prayer is the public worship of the assembled Christian congregations within churches and cathedrals using services taken from The Book of Common Prayer. Common Prayer does not refer to any kind of public prayer but only to that which is according to the form provided by this prayer book. This important principle has been enforced and underlined by the practice, which began in 1552, of printing the Act for the Uniformity of Common Prayer inside The Book of Common Prayer. The 1662 Act for Uniformity may be read in many printings & editions of the Prayer Book (1662), and explanations of it are offered in the twenty or more Annotated editions of The Book of Common Prayer that appeared in the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century (e.g., see The Prayer Book Interleaved with notes by W. M. Campion & W. J. Beaumont, 1866 and later editions)……

This excerpt is taken from the longer booklet