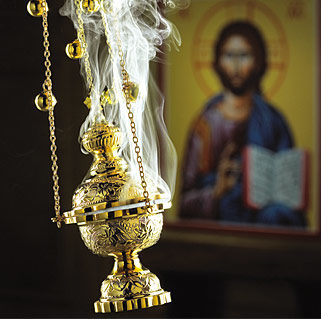

Incense in the Liturgy of the Church

(St. Barnasbas Newsletter August 2022)

For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same my name shall be great among the Gentiles; and in every place incense shall be offered unto my name … (Malachi 1:11)

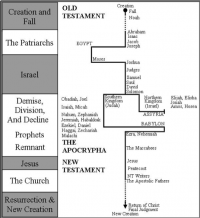

Love it or hate it, savour or choke, incense has been used in worship within the Judaeo-Christian Tradition for over 2500 years, and is still common in many liturgical parishes—including at St. Barnabas! The use of incense in Jewish rituals is set out in the Old Testament, particularly in Exodus 30, as directions given to Moses at the time of the exodus from Egypt. Moreover, we know from extra-biblical sources that its use continued from at least the 7th century B.C., sometimes together with various food offerings, as well as by itself as part of the twice-daily Temple rite and on the Day of Atonement until the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70. In the

Christian era, the use of incense was standardized when Christianity became the established faith of Rome, at the time of Constantine. The Liber Pontificalis of Pope Sylvester (314-355) lists a number of golden censers amongst the inventory of the furnishings of the churches built by Constantine. The first reliably recorded use of incense in Christian rituals was approximately A.D. 385 when it was used as part of the ceremonies of Holy Week at the cave of the Holy Sepulchre. Eventually, the use of incense became a prescribed part of the ritual of the Church. It was chiefly used at the Mass, where, in the Western Church, it was offered at the introit and the reading of the Holy Gospel (except at requiem Masses), and at the offertory and consecration. Another important occasion for the use of incense was the Gospel canticle during the morning and evening hours of the Divine Office.

But what about it’s use in English Christianity, specifically? Prior to the Reformation, the use of incense in English liturgy was similar to that on the continent. Thus, for example, the rites of Sarum, Hereford, Bangor, and York, all provided for the use of incense at one or more of the entrance rite, the reading of the gospel, and the offertory. In practice, the cost of incense at the time resulted in its rather limited use, which is why little controversial notice was taken of it at the time of the Reformation. Following the

Reformation, incense continued to be used in Anglican churches, as evidenced by historical records of churchwardens’ accounts showing the purchase of incense. There are also numerous specific records of ecclesiastical use of incense. Thus, for example, the chapel of Bishop Lancelot Andrewes housed “a triquetral censer, whereon the Clerk put incense at the reading of the First Lesson.” Incense is reported to have been used at the consecration of a church by Archbishop Sancroft in 1685, and at the coronation of George III in 1760. The Ritual Committee of the Lower House of Convocation declared, in 1866, that “the burning of Incense in a standing vessel had been practiced since the Reformation in some Churches and Chapels, Cathedral, Collegiate, Royal, Episcopal, and Parochial;” and that “instances might be found down to the middle of the last century.” The committee stated that ritual use of incense was illegal, but that there was no objection to burning it “in a standing vessel for the twofold purpose of sweet fumigation and of serving as an expressive symbol.” The question of the ritual use of incense did not become a cause for controversy until the rise of the Liturgical Movement in the 19th century when opponents and proponent wrote tracts, articles, and even books in support of their position. Those opposed claimed that the use of incense was unlawful because there was no provision for the use of incense in the rubrics of the 1662 Prayer Book. Proponents of incense showed from historical evidence that incense was, in fact, in use in the Church of England during the second year of the reign of Edward VI, i.e. January 28, 1548 through January 27, 1549. This study showed that, wherever there was no change in usage from 1548 to 1549, the rubrics are silent. In addition to historical continuity, what are the reasons for our ongoing use of incense in Christian religious ceremonial?

Aesthetic: while, in earlier times, the addition of some material which smelled pleasant when burnt was practical for the purpose of masking the unpleasant odours (including animal and human), a more nuanced evaluation suggests that, because liturgy is intended to appeal, insofar as possible, to all of the senses of the worshippers, magnificent surroundings and rich vestments which delight the sense of sight and music that gratifies the sense of hearing should be complement by pleasant aromas which appeal to the sense of smell.

Sacrificial: A number of the ingredients often used in incense were (and some still are) very expensive. The dedication of these costly materials to be burnt in honour of the deity was regarded as a form of offering of one’s substance.

Symbolic: The smoke of the incense, as it rose, was seen as a symbol of the prayers of the faithful. Scriptural examples include Psalm 141:2—”Let my prayer be set forth in thy sight as the incense, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice” and Revelation 5:8— “And when he had taken the book, the four beasts and four and twenty elders fell down before the Lamb, having every one of them harps, and golden vials full of odors, which are the prayers of saints.”

Psychological: The scent of burning incense may, in itself, have an effect upon the unconscious of the worshippers. One reason for this is that the sense of smell, being purely chemical, is the oldest and most primitive of the five senses, and hence a powerful vehicle for triggering associations and memories, both individual and collective. Another reason is that the scent may stimulate the autonomic nervous system, which produces hormones which affect the functions of the body, and which are also released when strong emotions are felt.