Confirmation Adult Manual 2019 volume 3 of 10

CHAPTER 3

ANGLICAN WORSHIP: THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER LITURGY AND PIETY

Introduction- Worship in the Anglican Tradition:

Worship is central to the identity of the Anglican tradition. From its beginnings in the Church of England worship united various factions into one church. Anglicanism is not confessional; beliefs are voiced through texts and actions of worship. The Book of Common Prayer provides a framework.

In 1549 the first English Book of Common Prayer united ancient materials with the theological understandings of that day and place. Each subsequent edition of the English Book of Common Prayer showed development of thought and practice to adjust here and there, at times moving away from its early practices, and then only to return to them.

Worship and Liturgy in the Anglican Tradition is rooted in many traditions.

The Celtic tradition with its appreciation of nature and mystical experiences (inspiring a sense of spiritual mystery, awe, and fascination,) “the mystical forces of nature” is an important foundation of the Anglican spiritual tradition. The form and structure of the Roman and Benedictine monastic traditions are also important. In worship we seek to encounter God in holy time and space.

The activity of worship is to worship God and gain strength through His Sacraments to be faithful witnesses for Christ; this is summed up in the prayer of The Prayer of Thankgiving following the Eucharist (page 83):

Let us pray.

ALMIGHTY and everliving God, we most heartily thank thee, for that thou dost vouchsafe to feed us who have duly received these holy mysteries with the spiritual food of the most precious Body and Blood of thy Son our Saviour Jesus Christ; and dost assure us thereby of thy favour and goodness towards us; and that we are very members incorporate in the mystical body of thy Son, which is the blessed company of all faithful people; and are also heirs through hope of thy everlasting kingdom, by the merits of his most precious death and passion. And we humbly beseech thee, O heavenly Father, so to assist us with thy grace, that we may continue in that holy fellowship, and do all such good works as thou hast prepared for us to walk in; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with thee and the Holy Ghost, be all honour and glory, world without end. Amen.

Worship involves the whole of life and the whole of each person

Anglican worship is incarnational, recognizing that all parts of our human self are heirs of the promise of salvation begun in Christ’s incarnation; we use all parts of our being (body, mind, spirit) to worship God. This includes the entire Church (Church Militant, Expectant, and Triumphant.) The seasons of the Church liturgical calendar draw the faithful into the story of faith. Various sacramental rites bring God’s presence and blessing into all areas of life. The use of sense, motion, and action in worship involves the whole person in worship. Our tradition embraces a myriad of opportunities to bring our lives and the life of God together.

Music in liturgy and worship

Any portion of the rites in the Book of Common Prayer may be sung or said. Because we have no confessional statement to guard our beliefs, the texts of hymns, songs, and anthems must conform to the standard of worship (The Book of Common Prayer). The Rector of the congregation is the final authority for the conduct of worship and music in a parish. The clergy are bound by canonical requirements that prevent innovations inconsistent with our received practices and beliefs.

The Book of Common Prayer and individual piety

The Book of Common Prayer is as much a tool for private piety as it is for corporate worship. Forms, including schedules for Scripture readings, for daily prayers at Morning, Noonday, Evening, and Compline, as well as other devotions, are found in The Book of Common Prayer. Other spiritual activities (such as rosaries, silent meditation, contemplative reading of holy texts) are also parts of the Anglican traditions of piety.

Conclusion

Anglican worship is comprehensive in that it can hold within itself many different and divergent elements: Catholic and evangelical, Individual and corporate. Anglican worship gives voice to our beliefs.

NOTE: Preface from The Oxford American Prayer Book Commentary

“The early Christians employed no books in their common worship except the Scriptures. Prayer was freely composed by the celebrant according to his own taste and ability, although the thoughts and aspirations expressed in them were more or less fixed by custom and tradition. There was no official hymn-book other than the Psalter, from which selections were chanted by appointed soloists or small choirs. By the beginning of the third century there began to appear short manual, known as Church Orders, which provided directions and suggested forms of prayer for the liturgical assemblies of the Church. The most notable example of such Church Orders, was the Apostolic Tradition by St. Hippolytus of Rome, composed about the year 200 or shortly before. The elaboration of the Church’s public rites and ceremonies that followed the cessation of persecution and the official recognition of Christianity by the state in 313…these texts were completely fixed as far as the essential structure of the liturgy is concerned, by the end of the sixth century…hence, there developed they system of codifying the several parts of a single type of service-prayers, chants, lessons, rubrics-in one collection. Thus arose the Missal, which contained all things necessary for the celebration of the Holy Eucharist through out the year; the Breviary for Daily Offices; the Manual or Ritual with the Occasional Offices; and the Pontifical, containing such services as were reserved for the Bishop…A reasonable degree of uniformity in common worship must of necessity presuppose full and active lay participation in the liturgy-all the more so in times such as the present, when population is mobile.” (Pages xii – xv)

Thought

Worship is central to the life of the Anglican tradition. An experience of Anglican worship is what initially draws many people into the fellowship of this Church. As we shall see, from the beginnings of the Church in England as a distinctive ecclesiastical body, it was the activity of worship that united various beliefs into one Church. In large part worship still identifies who we are more than any other factor.

The Continental Reformation established many confessions:

Continental Reformed: Zwingli’s Sixty-Seven Articles 1523 [1]; Ten Theses of Berne 1528 [1]; East Friesland Confession; Tetrapolitan Confession 1530; Synodical Declaration of Bern 1532 [2]; First Confession of Basel 1534; First Helvetic Confession (Second Confession of Basel 1536); Lausanne Articles 1536; Geneva Confession 1536; Zurich Consensus 1549; Emden Catechism 1554; Confession of the English Congregation at Geneva 1556; French Confession of Faith 1559; Confession of the Christian Faith 1559 [2]; Second Helvetic Confession 1562; Erlauthal Confession 1562; Hungarian Confession 1562; Heidelberg Catechism 1563; Belgic Confession 1566; Sendomir Consensus 1570; Wittenberg Catechism 1571; Confession of Nassau 1578; Bremen Consensus 1595; Sigismund Confession 1614; Canons of Dordt 1619, known collectively with the Heidelberg Catechism and Belgic Confession as the Three Forms of Unity.

As you can see, the Reformation had many moving elements within.

The Anglican tradition is not “confessional”…

We have no official systematic theology or officially defined set of beliefs other than those expressed in the Book of Common Prayer, which we voice through our common worship. For instance, one can say that Anglicans believe in one God who is a Trinity of persons not because we have an academic statement that says so but rather because when we worship we profess the Nicene or Apostles’ Creed, both of which witness to the Holy Trinity. In another instance, we believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and regard as mystery how that is accomplished beyond what is indicated by Eucharistic prayers (Christ was the word that spake it. He took the bread and break it; And what his words did make it. That I believe and take it. – spoken by Elizabeth when questioned on her beliefs on the Eucharist). Our beliefs are given voice by the content of our worship, which continues to re-enforce our beliefs. None of this is to say that all Anglicans have always worshipped in the same way any more than Anglicans have always believed exactly in the same way.

Worship in the Anglican tradition is grounded in the use of The Book of Common Prayer in its various national editions. The first English Book of Common Prayer was published in 1549. Its content was a mixture of ancient materials and the theological thoughts. Its real genius was that it provided a common English text so that priest and people could both take an active role in the worship of the Church. The prayer of the Church was in common, including all persons. Subsequent editions of The Book of Common Prayer leaned more toward traditional Catholic doctrines; sometimes the movement was toward principles of the Reformation Churches. The intent of all of the books was simply to have the people of England, regardless of their individual religious persuasions, worship together as one people in one Church.

As the British colonial empire spread across the globe so did the Church of England. With the Church went The Book of Common Prayer. And while they were rooted in their mother Church’s Book of Common Prayer, each jurisdiction of the Church developed its own unique version of the prayer book. In the modern era various national editions of The Book of Common Prayer and even subsequent editions of each individual Church’s prayer book can contain slight differences or shades of theology. From a historical perspective this is because some national Churches were founded by more Catholic minded missionaries, some by more Evangelical minded missionaries.

The history of worship in the Anglican tradition has been grounded in a common source of prayer for the Church (the prayer book) and has used the activity of worship to gather up and hold together a wide variety of beliefs and practices. The diversity of Anglican worship is experienced in many ways. The style of our worship can embrace the elaborate ceremonial of the Anglo-Catholic or “High Church” tradition or the Evangelical tradition, which is often referred to as “Low Church.”

Despite our English roots, worship of the Anglican Church in this day and age is done in many languages, including Spanish, French, Maori, Creole, African dialects, Portuguese, Japanese, Lakota Sioux, and Arabic to name a few. The Anglican Communion is a world-wide entity and our worship reflects that in musical styles, styles of liturgical vesture, and cultural accoutrements.

The roots of our worship drink from the ancient traditions of Celtic spirituality, with its appreciation for the Divine witness in the created world. Our system of daily devotions at morning, noon, evening, and night stems from the venerable Benedictine monastic tradition (can be found on www.commonprayer.org – hourly offices: Laudes, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline.) Our liturgies, the set forms of our worship, draw from the ancient traditions of the undivided Church catholic as well as from Reformation principles. We value Scriptures in all of our worship.

The essence of our liturgies is an encounter with the living God, during which we acknowledge and give thanks for all that God has done for us and seek God’s strengthening grace to continue in the holy fellowship of the Church and draw others into the community of faith. This sentiment is expressed very eloquently in what for many is a favorite prayer from the prayer book (page 19 & 33):

“Almighty God, Father of all mercies, we, thine unworthy servants, do give thee most humble and hearty thanks for all thy goodness and lovingkindness to us, and to all men; (particularly to those who desire now to offer up their praises and thanksgivings for thy late mercies vouchsafed unto them.) We bless thee for our creation, preservation, and all the blessings of this life; but above all, for thine inestimable love in the redemption of the world by our Lord Jesus Christ; for the means of grace, and for the hope of glory. And, we beseech thee, give us that due sense of all thy mercies that our hearts may be unfeignedly thankful; and that we show forth thy praise, not only with our lips, but in our lives, by giving up our selves to thy service, and by walking before thee in holiness and righteousness all our days; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with thee and the Holy Ghost, be all honour and glory, world without end. Amen.”

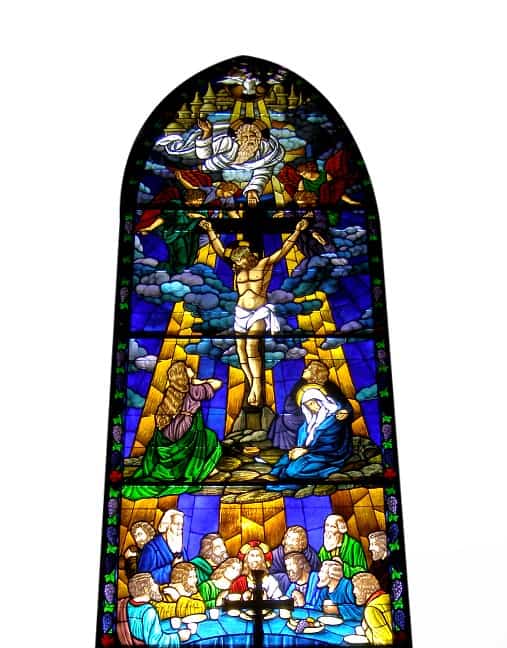

In worship we encounter the God of our salvation through the Scriptures that are read and shared. In worship we remember Christ’s sacrifice on the cross for the reconciliation of the world and celebrate the gift of grace. Through sacramental acts such as Baptism and the Holy Eucharist, we are drawn into the Divine life of the Body of Christ which is the Church.

The Anglican tradition is deeply incarnational, that is to say we believe that by the Incarnation of Christ, all of our lives are blessed. Our physical selves, as well as our spiritual selves, are participants in the salvation Christ offers, and both to be open to God’s activity.

In worship, the times and seasons of all our lives are brought into the presence of God and Christ’s Church. The church calendar divides the year into seasons and days of special commemoration. Advent draws us into the mystery of the first and next coming of Christ into this world. The Gesima Season (Pre-Lent) prepares us as it acts as a transition from a time of Joy into a penitential season and the Lenten Season helps us to participate in the suffering and passion of Christ. Easter lifts us to celebrate God’s re-creation of the world through the death and resurrection of Christ. Days which commemorate events in the life of Christ and the Church, such as Pentecost, the Ascension, and the Epiphany of Our Lord, helps us to grasp the fullness of the story of our faith.

Saints’ days and special commemorations give us concrete examples of lives lived in faithfulness to God and instill in us the hope that we, too, can live faithfully and even valiantly for Christ. Scripture lessons, prayers, and brief readings for every official commemoration are found in a book entitled Lesser Feasts and Fasts.

In the corporate worship of the rites of Marriage, Ordination, Laying on of Hands for Healing, Confirmation, Burial, we acknowledge that all of our life and all parts of our lives belong to God.

We also worship “incarnationally.” Our worship provides our bodies as well as our minds with the opportunity to be engaged in worship. We stand, sit, and kneel. We sometimes bow or genuflect. We use the sign of the Cross. Our worship spaces are often beautifully adorned with fabrics and candles. Our ears and voices are engaged in worship by music. In the laying on of hands the sense of touch conveys the grace of God. We can even use the sense of smell in worship by the use of incense or oil of chrism, or candle wax.

For the Anglican tradition, the whole world is part of God’s holy creation. Our worship includes provisions for the Blessing of Homes, the Blessing of Fields, as well as the blessing of articles created to enhance the beauty of holiness in worship. Near the calendar date for the commemoration of St. Francis, it is not uncommon to find a service for the Blessing of Animals.

In worship we assemble as the whole people of God. Young, old, rich, poor, male, female, lay, and clergy, all are made one by the spirit of the Risen Christ and all worship together. We are united by worship with the Church Universal as well, as our prayers and praises are joined with the prayers and praises of those who have gone before us in the faith, all those who will come after us, and with the angels whose delight it is always to worship God. We sing with them one hymn of praise.

This brings us to the role of music in our liturgy. The Book of Common Prayer also points to the importance of the texts of hymns and anthems in our worship. Remembering that our theology is expressed primarily through worship, it makes sense that we do not allow just anything to be sung or said during worship. As The Book of Common Prayer instructs,

“Hymns referred to in the rubrics of this Book are to be understood as those authorized by this Church. The words of anthems are to be from Holy Scripture, or from this Book, or from texts congruent with them” (BCP p. 14).

Music, especially hymns, is how the theology of our tradition is made clear and immediate to the people. They have been called “the theological texts of the people.” Care should be taken then that hymns and songs are never present just because we like to sing them, but because they serve to draw out the meaning of the scripture texts or commemorations of the day or to give us words to respond to them.

By Canon Law the ultimate responsibility for the content and conduct of the worship of the parish Church rests exclusively with the Rector or Priest in Charge. Even then he or she is not free to make innovations or changes to the Church’s liturgical forms. Canon Law requires that they must conform to the rubrics (instructions) of The Book of Common Prayer. By having this requirement, the Church safeguards the people from the whims and personal convictions of individual members of the clergy and insures that the breadth of our tradition is maintained from the largest cathedral to the smallest mission.

The worship of the Anglican tradition is obviously corporate and public but it is also private. We hesitate to divide one from the other because they are necessary to each other. Each Anglican is encouraged to have a personal discipline of prayer and study called a Rule of Life. Here, too, The Book of Common Prayer is our guide. Author Martin Thornton has written:

To the seventeenth-century layman the Prayer Book was not a shiny volume to be borrowed from the shelf on entering the church and carefully replaced on leaving. It was a beloved and battered personal possession, a lifelong companion and guide, to be carried from church to kitchen, to living room, to bedside table.

The prayer book provides the guides for a detailed and systematic reading of Scripture in the Daily Office lectionary as well as the three year cycle of weekly readings for the Sunday Eucharist. It also provides numerous forms for devotions for families and individuals. It contains the Psalms which are some of the best devotional reading Christians can have. The Book of Common Prayer is to be used at home as well as in the Church.

The Book of Common Prayer, as important as it is to our tradition, is not the limit of our lives of prayer and devotion. From the foundation of corporate prayer and liturgy, Anglicans worldwide have always valued their own traditions of individual piety. Many Episcopalians pray the Rosary in either its traditional Marian form or in the newer tradition of Anglican Prayer Beads. Silent contemplative prayer, the use of lectio divina (contemplative reading of Scriptures and other sacred texts), walking the labyrinth (difficult complicated passages), speaking in tongues, praying in the Spirit, pilgrimages, retreats, silent days, all have a place in our tradition. All have are helpful as individuals work toward deepening their spiritual lives.

The Church’s calendar of seasons, feasts, and commemorations can also be brought closer to the heart by observing religious traditions and customs in the home, thus making each home a chapel. This is especially helpful when there are young children in the home as it helps them understand that home is as much a part of religious life as is the church building. Examples of these home based liturgies might include using an Advent wreath, setting out cookies for St. Nicholas, flying a kite on the Feast of the Ascension, or celebrating each person’s baptismal birthday with a cake and small religiously themed presents. The limits to what we do and find helpful to us spiritually are bounded only by our imaginations and our willingness to experience new avenues of spiritual refreshment.

Worship in the Anglican tradition is comprehensive, that is to say that it encompasses many things. It can contain the Catholic tradition as well as the Evangelical. It is private and corporate. It is as unique as each worshipper and at the same time as universal as Christ’s One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church (the four marks of the Church.) It is grounded in the traditions of The Book of Common Prayer and grows from there. It is found in the meeting of the Church for the weekly Sunday celebration of the Resurrection and in the home liturgies that call God’s presence into every moment of every day.

Our worship is made particular by the traditions of each local parish and at the same time witnesses to the universal Gospel of the Risen Christ. Worship is what tells others who we are. It is also how we tell ourselves and those who come into our community who we are and what we believe. We are, in the major part, defined by our worship and liturgy, as we have always been, and as we always shall be.

END OF CHAPTER 3